Superior Vena Cava Syndrome

A 33-year-old man with a previous medical history of well-controlled HIV on antiretroviral therapy and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) presented to the bone marrow transplant (BMT) clinic for evaluation of relapsed lymphoma.

He was found to have diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) consistent with primary mediastinal large-cell lymphoma one year before presentation and underwent six cycles of dose-adjusted EPOCH-R (etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, rituximab) chemotherapy. Positron emission tomography (PET) computed tomography (CT) performed one month after completion of treatment showed no evidence of disease and the patient was considered to be in clinical remission. However, he was found to have new anterior cervical lymphadenopathy on a follow-up PET CT scan and was referred for BMT evaluation.

He endorsed progressive neck and bilateral arm swelling associated with pharyngeal dysphagia, dyspnea, and worsening headache when lying flat for the past four weeks. He denied syncope, dizziness, vision changes, fever, chills, night sweats, cough, hoarseness, dyspnea on exertion, chest pain, palpitations, or other symptoms.

Upon examination, his vital signs were within normal limits. He showed no acute distress and was alert and oriented in person, time, and space; he showed no facial plethora, asymmetry, or facial droop. His pupils were 2 mm bilaterally and reactive to light, his extra ocular movements were intact, and he had no motor or sensory abnormalities. He was breathing comfortably and had no stridor, respiratory distress, or accessory muscle use. Lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally. His heart sounded audible – there was no murmur or pericardial rub. Positive findings included facial and bilateral upper extremity edema, bilateral jugular venous distention, and dilated collateral veins on right chest wall and right shoulder. Two lymph nodes approximately 2 cm in size were palpable on the right anterior cervical chain. No hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, and no other palpable lymphadenopathy were observed. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

What is the most appropriate next step in this patient’s management?

- Chest X-ray and follow-up in one week

- Refer to the emergency department

- CT scan of the chest and follow-up in one week

- Refer for lymph node biopsy and follow up with the results

Answer: B

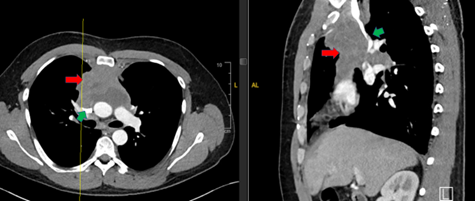

He was referred to the emergency department and underwent a CT scan with intravenous contrast (Figure) showing severe compression of the superior vena cava (SVC) secondary to anterior mediastinal mass, and a right internal jugular vein thrombus. He was admitted for management of superior vena cava syndrome (SVCS).

Figure. Green arrow: superior vena cava compressed by mediastinal mass. Red arrow: anterior mediastinal mass. Image used with approval from Icahn School of Medicine.

SVCS is a constellation of signs and symptoms secondary to extrinsic compression or intrinsic obstruction of the SVC and is considered an oncologic emergency. Infectious etiologies like syphilis and tuberculosis were the most common causes until the advent of adequate antibiotics. In the current era, intrathoracic malignancies account for 60 to 85 percent of SVCS cases, followed by thrombosis or stenosis secondary to central lines or medical devices.1

The three most common malignant causes are non-small cell lung cancer in approximately 50 percent of cases, followed by small-cell lung cancer in approximately 25 percent of cases, and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (particularly PMBCL with sclerosis but also in other DLBCL and lymphoblastic lymphomas)2 in approximately 10 percent of cases. Other rare etiologies include germ-cell cancer, thymoma, mesothelioma, and others.3

Pathophysiology

The SVC forms from the conjunction of the right and left brachiocephalic trunks, carrying venous blood from the head, neck, arms, and upper torso. It constitutes around one-third of the venous return to the heart.2 Obstruction of the SVC leads to backflow and vascular congestion of the brachial, cervical, and cerebral venous systems, leading to the typical clinical presentation. The vascular obstruction is relieved by flow through the azygos-hemiazygos pathway or by formation of new venous collaterals.1,2

Clinical Presentation

Common signs and symptoms in descending order of frequency include facial edema, distended veins in the chest/neck, dyspnea, cough, arm edema, facial plethora, headache, and syncope. Rare symptoms suggestive of life-threatening complications include dizziness, confusion, vision changes, stridor, and obtundation.3

SVCS is a clinical diagnosis.4 It is most frequently mild or asymptomatic but can also cause life-threatening airway or cerebral edema.5 Adequate clinical history should include the duration and progression of symptoms, and the patient’s medical, oncological, and surgical history, as well as the presence of intravascular devices. A good physical examination can help rule out differential diagnoses such as congestive heart failure and pericardial effusion.2,3

Management

Once the diagnosis is established, the first step is to identify signs of life-threatening cerebral edema, laryngeal edema, or hemodynamic compromise. If present, initial stabilization (secure airway, breathing, and circulation) takes priority.6 Intubation might be challenging and medication infusion through the upper extremities may be unreliable or worsen vascular congestion.7

While there are no evidence-based guidelines for the management of SVCS, a severity score has been proposed to guide management based on clinical factors.1,5 General measures like head and chest elevation and oxygen for hypoxia should be maintained. Application of diuretics and steroids has been described, but high-quality evidence supporting their use is lacking.1-3

Acknowledgement: This article was edited by Madeline Niederkorn, PhD, and Leidy Isenalumhe, MD, MS.

Table. Classification and management of SVCS.

| Grade | Findings | Management |

| 0 | Asymptomatic – radiographic evidence of SVC obstruction |

Workup and etiology-directed treatment |

| 1 | Mild – edema in head or neck, plethora, cyanosis |

Regular care and elective CT Etiology-directed workup and treatment |

| 2 | Moderate – edema in head or neck with functional impairment (dysphagia, cough, head, jaw, eyelid movement, visual disturbances) | Same as 1 |

| 3 | Severe – mild or moderate cerebral edema (headache, dizziness), mild or moderate laryngeal edema, or diminished cardiac reserve (syncope after bending) |

Intermediate care with close monitoring Urgent CT Thrombosis: start anticoagulation Tumor compression: stent Etiology-directed workup and treatment |

| 4 | Life-threatening – significant cerebral edema (confusion, obtundation), significant laryngeal edema (stridor), or significant hemodynamic compromise (syncope without provocation, hypotension, renal impairment) |

Emergency care Emergent CT Thrombosis: thrombolysis, anticoagulation Tumor compression: urgent stent Etiology-directed workup and treatment |

| 5 | Fatal – death |

N/A |

Adapted from Yu et al.5

After initial stabilization, imaging should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis and assess the extent of the underlying cause. Contrast-enhanced CT is considered the method of choice due to its high sensitivity and specificity.1,6

If thrombosis is the etiology, anticoagulation should be initiated, and a multidisciplinary team should be involved to evaluate the need for invasive procedures. Removal of indwelling catheters should be considered.1

If malignancy is the underlying cause, obtaining histologic diagnosis and involving a multidisciplinary team will be essential to determining the need for invasive therapy and to guide further oncologic treatment. In stable patients (grade 0-2), directed treatment can be started after pathologic confirmation of the disease. Patients with severe symptoms (grade 3 and above) and known radio- or chemotherapy-sensitive tumors (e.g., lymphoma) could be treated with any of these options. Endovascular stenting should be considered in patients with severe acute symptoms and unknown histologic diagnosis.1-3,5

Case Resolution

The patient was considered to have grade 3 SVCS due to history of headache. He was admitted for further workup and treatment. He was started on anticoagulation due to right internal jugular thrombus. He was evaluated for surgery by the Vascular and Cardiothoracic team; noninvasive procedure was deemed necessary.

He underwent a lymph node biopsy and was found to have DLBCL. He was promptly started on steroids and R-ICE (rituximab, ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide phosphate) chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplant. He had significant response and improvement of his symptoms as soon as two days after starting treatment.

- Klein-Weigel PF, Elitok S, Ruttloff, A, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome. Vasa. 2020;49(6):437-448.

- Lepper PM, Ott SR, Hoppe H., et al. Superior vena cava syndrome in thoracic malignancies. Respir Care. 2011;56(5):653-66.

- Wilson LD, Detterbeck F, Yahalom J. Superior Vena Cava Syndrome with Malignant Causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(18):1862-1869.

- Higdon ML, Atkinson CJ, Lawrence KV. Oncologic Emergencies: Recognition and Initial Management. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(11):741-748.

- Yu JB, Wilson LD, Detterbeck FC. Superior vena cava syndrome: a proposed classification system and algorithm for management. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;3:811 814.

- Spring J, Munshi L. Oncologic Emergencies: Traditional and Contemporary. Crit Care Clin. 2021;37(1):85-103.

- Chaudhary K, Gupta A, Wadhawan S, et al. Anesthetic management of superior vena cava syndrome due to anterior mediastinal mass. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012;28(2):242-6.

Acknowledgement: Edited by Dr. Madeline Niederkorn and Dr. Leidy Isenalumhe.

Dr. Ricardo Ortiz and Dr. Malone indicated no relevant conflicts of interest