Answer: D

HLH is a life-threatening syndrome resulting from uncontrolled hyperinflammation. It is most prevalent among children up to three years of age, although it can occur in all age groups. The immune dysregulation in HLH results from an inability of CD8+ T cells or NK cells to eliminate the source of antigenic stimulation and quench the inflammatory response. This leads to persistent activation of macrophages, which accelerates the progression of the disease via the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and phagocytosis of the patient’s blood cells. The abnormal activation of the immune system can lead to multiorgan failure and death. HLH has been historically divided into primary (childhood-onset, familial, without any obvious trigger) and secondary (adult-onset, usually diagnosed in patients with concomitant infection, malignancy, rheumatologic, or immunodeficiency syndrome) categories. However, according to the recent recommendations from the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis, the traditional classification does not capture the range of clinical phenotypes observed in HLH and may lead to misdiagnosis. For instance, some cases of familial childhood-onset HLH are usually triggered by an EBV infection (e.g., ITK, CD27, CD70, or MAGT deficiency). Conversely, 14 percent of adult patients with HLH secondary to rheumatologic disease or malignancy have been found to carry hypomorphic HLH-related mutations. Therefore, the most important task of the treating physician is to differentiate between true HLH disease and HLH mimics, such as atypical infections, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, multicentric Castleman disease, drug reactions, and storage disorders.

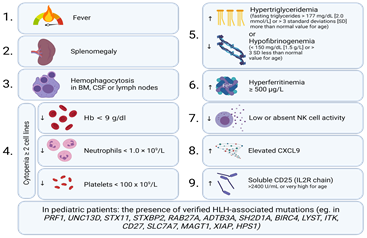

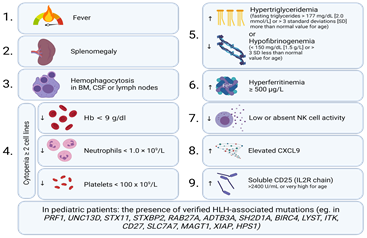

Based on the clinical and laboratory findings (fever, splenomegaly, hemophagocytosis, pancytopenia, hyperferritinemia), the patient in this case was diagnosed with EBV-induced HLH per the diagnostic criteria used in the HLH-2004 trial.1 The modified HLH-2004 criteria2 are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Diagnostic criteria for HLH. Five of nine criteria should be met to diagnose HLH. Genetic testing can aid in diagnosing HLH in pediatric patients. Created with BioRender.

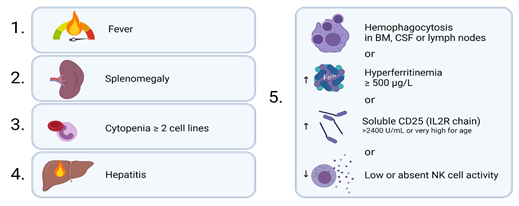

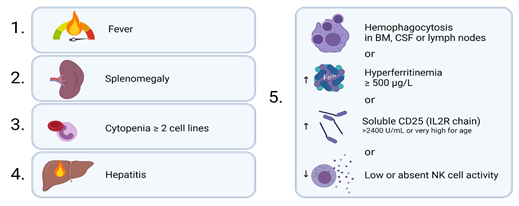

It is not always necessary to meet the above-mentioned criteria to initiate treatment like when a patient is too sick to undergo a biopsy. In such cases, simplified criteria such as those featured in Figure 3 may be sufficient to diagnose HLH in the appropriate clinical context.1,3

Figure 3. Simplified criteria for diagnosis of HLH. The patient must have three of four clinical findings (fever, splenomegaly, cytopenias, hepatitis) plus an abnormality of one out of four immune markers (hemophagocytosis, increased ferritin, increased sCD25, low or absent NK cell function).3 Created with BioRender.

To estimate the probability of HLH, a scoring system “HScore” has been developed. This patient scored 194 points, thus conferring an 80 to 88 percent probability of HLH.4

MAS is ruled out since it is mainly associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. In this case, there was no evidence of rheumatological disease. A diagnosis of ALPS is also eliminated. Although patients with ALPS may mimic findings of HLH, such as hepatosplenomegaly and cytopenias, the patients usually do not present with high ferritin levels and it is not associated with EBV infection. Kawasaki disease, characterized by fever, rash, and lymphadenopathy, is also ruled out. Typical findings include elevated triglycerides, conjunctivitis, mucositis, and coronary artery aneurysm, which are less common in HLH. Of note, Kawasaki disease can also act as a trigger to HLH, thus its diagnosis does not exclude HLH. Therefore, a Kawasaki patient with “atypical” symptoms or not responding to intravenous immunoglobulin therapy, should be evaluated for HLH. Finally, despite having common characteristics, such as fever, liver function abnormalities, and rarely hemophagocytosis, DRESS does not induce extremely high ferritin release and cytopenias, which are found in patients with HLH.

Treatment

The goal of therapy in HLH is to suppress life-threatening inflammation. Treatment should not be delayed due to pending genetic or immune deficiency tests, as HLH progresses quickly and is commonly fatal with a 52 percent risk of death if left untreated.5 If HLH is triggered by an acute infection or other condition such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis or malignancy, treatment of the primary cause may remove the stimulus for immune activation.

The patient was treated according to the HLH-20046 protocol with 14 weeks of cyclosporine A, hydrocortisone, and etoposide. Significant improvement in the laboratory parameters and clinical status was achieved. Unfortunately, one month after treatment discontinuation, the patient presented to the emergency department with fever, high ferritin, liver enzyme and fibrinogen levels, coagulopathy, and high EBV replication (500,000 DNA copies/ml). A bone marrow biopsy revealed hemophagocytic cells.

She was diagnosed with relapsed HLH triggered by EBV reactivation. Treatment with the HLH-2004 protocol was initiated with the addition of rituximab to ablate the reservoir of EBV in CD20+ B cells. Genetic testing did not reveal any pathogenic HLH-related mutations. Due to an insufficient therapeutic response and disease relapse, the patient underwent allogeneic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), complicated by late acute graft-versus-host disease controlled with corticosteroid therapy. The patient has been followed up for the past five years and remains disease-free.

Conclusion

HLH is a life-threatening inflammatory condition affecting both pediatric and adult patients. There are both formal and simplified diagnostic criteria, and elucidating the causative trigger can aid in establishing the correct diagnosis. Treating HLH is challenging and should be based on the severity of symptoms as well as the triggering factors. A vicious cycle of hyperinflammation and multiorgan failure should be prevented using immunosuppressants and cytostatics. Delay of treatment decreases survival rate. In patients with persistent or recurrent HLH, or defects within the immune system that predispose to HLH, allogeneic transplantation can be curative.

- Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, et al. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011;118:4041-4052.

- McClain KL, Eckstein O. Clinical features and diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. UpToDate. Last updated Apr 19, 2021.

- Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;2009:127-131

- Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and valudation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2613-2620.

- Janka G, Imashuku S, Elinder G, et al. Infection- and malignancy-associated hemophagocytic syndromes. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1998;12:435-444.

- Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131.

A 2.5-year-old girl with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with febrile seizures and a six-day history of fever above 102°F treated hitherto with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid without any improvement. No weight loss or unusual fatigue were reported.

A 2.5-year-old girl with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department with febrile seizures and a six-day history of fever above 102°F treated hitherto with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid without any improvement. No weight loss or unusual fatigue were reported.